Profit Shifting Case in Indonesia Highlights Need for Improved Tax Collection

May 19, 2021

By Forum Pajak Berkeadilan*, Woods & Wayside International, and Global Financial Integrity

Indonesia, like many other countries, is suffering from a prolonged health crisis and economic fall-out caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. With a 2% decline in GDP, Indonesia’s economy contracted last year for the first time since 1998. State revenue has predictably dipped from the economic slow-down, while the government has increased spending to address the health emergency and to stimulate the economy. Concern over the resulting budget deficit in 2020 has drawn greater attention to ways that Indonesia can improve its persistently unimpressive tax collection rate, which at 11.9% of GDP is among the lowest in the region.

Within this context, a coalition of 25 Indonesian and international civil society groups published a report in November 2020 on profit shifting in the export of pulp from Indonesia. On a global scale, profit shifting and trade misinvoicing are pernicious drains on government revenue, causing an estimated $100 billion or more in annual tax losses, often through illicit financial flows for which few are ever held accountable.

For natural resource-rich countries like Indonesia, the loss of tax revenues caused by such illicit flows can be the difference between a nation harnessing its natural wealth for the benefit of all its citizens and letting it be siphoned into offshore accounts owned by a select few. Profit shifting practices have been a major contributor to the outflow of wealth from developing countries to advanced economies.

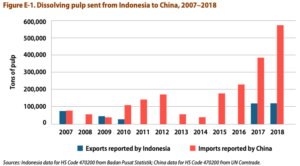

The civil society report — The Macao Money Machine: Profit Shifting and Tax Leakage in Indonesia’s Pulp Exports — documents apparent profit shifting practices in Indonesia’s wood pulp sector that may have caused tax losses for Indonesia exceeding US$150 million across a dozen years, 2007-2018. The starting point of the report was observing a significant gap between Indonesia’s reported exports of dissolving pulp and China’s reported imports of the same commodity from Indonesia (see Figure E-1).

Analysis of this gap uncovered an apparent deception: Indonesia’s dissolving pulp exports were being reported – and priced – as lower-value paper-grade pulp. The actual product – dissolving pulp – is a type of pulp used in the production of textiles, such as viscose rayon clothes and medical masks. Moreover, the shipments were not sold directly to buyers in China but rather through related-party marketing companies based in low-tax jurisdictions such as Macao and Singapore.

The marketing companies in Macao and Singapore – reportedly owned by the same beneficial owner, Sukanto Tanoto and members of his family, as the pulp mills in Indonesia – apparently were able to make substantial profits on these transactions by reclassifying the shipments as dissolving pulp and selling them to companies in China at significantly higher market-rate prices. Had the exports from Indonesia been appropriately priced for the product that was sold, the vast majority of profits earned by the Macao- and Singapore-based companies apparently would have been reported as taxable profits in Indonesia and subject to Indonesia’s corporate tax rates.

The Macao Money Machine estimates that dissolving pulp producers’ apparent use of profit-shifting practices had the effect of under-stating their revenues in Indonesia by over US$650 million between 2007-2018. In hypothetical terms, if it is assumed this full amount were taxed at the statutory corporate income tax rate, Indonesia’s fiscal authority could potentially have collected as much as US$168 million from the companies involved.

The organizations publishing the report emphasize that they do not know the particular tax situation or the effective tax rates of the Indonesian companies (PT Toba Pulp Lestari, PT Intiguna Primatama, PT Riau Andalan Pulp and Paper) or affiliated corporate groups (APRIL Group and Royal Golden Eagle) that apparently used such practices; and the report does not allege that any of the companies or individuals named have committed legal violations. Nonetheless, the report notes that if the Indonesian government “were to determine that [the companies involved] had understated taxable revenues, collection of these could represent a significant boost to tax collection and send a powerful signal to Indonesia’s corporate sector.” The case could take on a larger significance if the government uses this to build momentum for a broader crackdown on profit shifting practices in Indonesia’s lucrative natural resource industries.

Beyond the case study detailed in The Macao Money Machine, Global Financial Integrity has documented a larger trend of misinvoiced exports and imports that saps government revenue in Indonesia. According to a country-level report published by GFI in 2019, trade misinvoicing caused estimated revenue losses of US$6.5 billion for the Government of Indonesia in 2016. On a global level, GFI estimated a value gap of US$817.6 billion in 2017 attributable to trade misinvoicing between 135 developing countries and the 36 advanced economies.

Following publication of The Macao Money Machine in November 2020, Indonesia’s Directorates General of Customs and Tax convened a meeting with members of the civil society coalition, and announced it would follow up the case documented in the NGO report. Effective coordination between the tax and customs authorities is needed for the government to verify whether companies are fairly and accurately reporting their taxable revenues and to ensure that export prices legitimately reflect the value of the products being shipped.

More generally, this kind of inter-agency coordination would go a long way toward ensuring that companies operating in Indonesia’s natural resource sectors cannot use trade misinvoicing and/or abusive transfer pricing schemes to avoid or evade paying corporate tax to the Government of Indonesia. This, in turn, will allow Indonesia to improve funding for essential government services and to minimize the health and economic consequences of the pandemic.

*Forum Pajak Berkeadilan, or Tax Justice Forum, is a coalition of NGOs in Indonesia that includes Prakarsa, Indonesia Corruption Watch, Transparency International Indonesia, Publish What You Pay Indonesia, International NGO Forum on Indonesian Development, FITRA, LOKATARU, Indonesian Legal Roundtable, Indonesia for Global Justice, Auriga Nusantara, YLKI, and ASPPUK.