Free-For-All Zones: The Case of Dubai

By Lakshmi Kumar, August 5, 2020

Global Financial Integrity (GFI) was proud to contribute to the July 2020 report ‘Dubai’s Role in Facilitating Corruption and Global Illicit Financial Flows’ from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The contribution, Chapter 3 of the report, examined the role of free zones in Dubai as gateways for illicit financial flows and how a lax regulatory climate fosters a fertile environment for a multitude of illegal activities. Drawing on the 2020 Mutual Evaluation Report from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), it is clear that much of the analysis is substantiated by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) government data submitted on supervisory and law enforcement efforts around money laundering and terrorist financing, providing additional concrete evidence of the myriad problems with Dubai’s administration of its free zones.

Free zones are “designated areas within jurisdictions in which incentives are offered to support the development of exports, foreign direct investment (FDI), and local employment.” These incentives include exemptions from duty and taxes, simplified administrative procedures and the duty free importation of raw materials, machinery, parts and equipment. These same incentives also mean a reduction in “finance and trade controls and enforcement, creating opportunities for money laundering and the financing of terrorism”. As detailed in a previous GFI blog and in Chapter 3 of the report, the role of free zones in facilitating illicit activity including proliferation financing, organized crime, terrorist financing, and drug trafficking is well-documented both in Dubai and elsewhere. In many ways, the free zone incentive is a double-edged sword.

In February 2020, the FATF published its Mutual Evaluation Report on the UAE. In a departure from its last report on the country in 2008 where the FATF was only able to carry out “a rudimentary sampling of laws within the free zones,” the new evaluation aims to provide a more authoritative account of the laws, supervisory and oversight mechanisms and anti-money laundering (AML) vulnerabilities of the UAE’s free zones. This change in evaluation approach is reflective of the growing international recognition around the risks of illicit financial flows from free zones. Recent reports from the Organization for Economic Co-operation & Development and the World Customs Organization in 2019, as well as work by journalists and civil society have called attention to the need for clear definitions, mapping of free zones and well-defined policy solutions.

The fundamental premise on which the FATF assessment of UAE’s free zones is based is that there are 29 “commercial free zones’” and two “finance free zones.” This could arguably lead to the conclusion that there are in total “31 free zones” within the UAE. What is especially telling is that nowhere within the 288 pages of the evaluation does the FATF actually state the total number of free zones within the UAE – it is always careful to state that there are 29 of one type, and two of the other. This qualifying language is important, because it is used to narrowly specify the type of free zone without committing the FATF to an assessment of the total number of free zones within the UAE.

The FATF evaluation also does not actually address the issue of what qualifies as a “commercial free zone,” a “financial free zone,” or more broadly a “free zone.” In its only dedicated report examining the money laundering vulnerabilities of free trade zones in 2010, the FATF addresses the classification and definitional issues around the topic by stating that the term ‘free trade zones’ can be known by several other names, including: “free zones, freeport zones, port free trade zones, foreign trade zones, e-zones, duty free trade zones, commercial free trade zones, export processing zones, logistic zones, trade development zones, industrial zones/parks/areas, hi-tech industry parks, hi-tech and neo-tech industrial development zones, investment zones, bonded zones, special economic zones, economic development zones, economic and technological development zones, resource economic development zones and border economic cooperation zones”. Including all these other categories for the purposes of the evaluation would have significantly raised the total number of free zones as identified in the report to around 45 free zones in the UAE, of which about 30 are located in Dubai.

This analysis around the identification of the correct number of free zones and the appropriate categorization may come across as pedantic. But in truth, it has serious implications. While much attention is paid to the more well-known free zones, like Jebel Ali or the Dubai Multi-Commodities Centre, the real concern is that illicit activity through less public free zones may be overlooked. For instance, Dubai’s Cars and Automotive City Zone (DUCAMZ) is one of the largest re-exporters of used cards to Asia and Africa. Used cars have historically played a central role in laundering money, as well as serving as a prime trade-based money laundering (TBML) vehicle to hide the movement of drug proceeds. In instances outside the UAE, fictitious free zones like the Enterprise Free Zone in Banjul, Gambia were created to help a London-based company registration firm create multitudes of ghost corporations that helped, amongst others, the Iranian State Oil Company and the Italian mafia conceal their activities. These risks highlight both the critical importance in framing a clearer conceptual understanding of the term “free zone,” as well as an accurate registry and mapping of free zones globally.

In the annex of the Carnegie report, GFI attempted to compile a list of the free zones present within the UAE. The interactive map shown below allows the user to toggle between the identified free zones within the seven Emirates:

Map 1: Charting the UAE’s Free Zones

Source: Global Financial Integrity, 2020.

Some of the challenges with accurately mapping free zones anywhere in the world is the myriad names under which the free zones operate, as well as the absence of any international register, or even national register, of the zones. In the case of the UAE and Dubai, additional challenges include:

- Some free zones in Dubai have websites while others do not, despite having been operational for over a decade. For example, DUCAMZ was launched in 2000 to sell cars to the local markets, as well as re-export used cars internationally. The zone is supposed to be managed by the Jebel Ali Free Zone Authority. Yet there is no website for the zone, just numerous consultancies offering their services to register a company within the zone.

- Some of the free zones are supposedly still under construction, but there are already companies operating out of them. For example: the Dubai Energy and Environment Park (EnPark) was established in 2006 to develop the clean and alternative energy sector, and is still under construction. No website exists for the zone, but multiple consultancies offer their services in helping set up a company within the zone. Additionally, consultancies offering their services often describe it as free zone located inside the Dubai Biotechnology and Research Park (DuBiotech), but regulated by the Dubai Technology and Media Free Zone authority, adding additional layers of complexity and confusion.

- Over time, some of the free zones have merged, while others have spawned free zones within free zones. In the case of Enpark, the website for the Dubai Science Park indicates that Enpark would operate under Dubai Science Park. It isn’t clear if Enpark is therefore a free zone within another free zone, or if EnPark and DuBiotech have merged to become Dubai Science Park. While the press release announcing this provides no date, a report referenced in the press release would indicate that this merger or nesting arrangement was announced in 2015

Obfuscations such as these place significant limitations on the ability to accurately quantify and map free zones within the UAE.

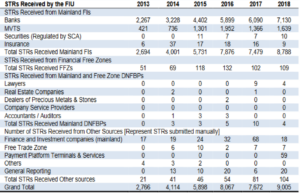

As Chapter 3 highlights, it is only within the last decade that free zones have been required to share financial intelligence information with the UAE Central Bank on transactions suspected of having links to money laundering or terrorist financing. Data provided by the UAE authorities (see Table 1 below) to the FATF evaluation team reveals that the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) and the Dubai Multi-Commodities Centre (DMCC) together only submitted 109 Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs) in 2018, a ludicrous number given the massive scale of assets under management and financial transactions passing through these zones. In 2019, the DMCC recorded US$35 billion in annual trade flow.

That same year, DIFC managed US$178 billion in banking assets and US$424 billion for the wealth and asset management industry, provided US$99 billion in lending, earned revenues of US$228 million and achieved an operating profit of US$139 million. The DIFC is also home to the largest cluster of financial institutions anywhere in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia region. This makes the small number of STRs filed by these two financial free zones especially glaring. Yet, even with this scale of financial activity, it is not clear that there is a strong impetus to create a robust compliance culture.

Similarly, Table 1 below, reproduced from the 2020 FATF report, shows that designated non-financial businesses (DNFBs) in the free trade zones submitted a paltry seven STRs in 2018. Interestingly, the table uses the term “free trade zones” and not “free zones” or “commercial free zones”. It is unclear if this was an oversight, or if the data represented here is from a larger or possibly more restricted set of zones. The FATF report itself provides little clarity on this matter.

Table 1: Suspicious Transaction Reports received by the Financial Intelligence Unit – UAE

Source: FATF – United Arab Emirates Mutual Evaluation Report (2020).

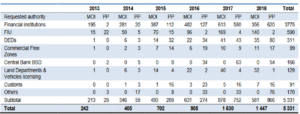

As highlighted in Chapter 3, Dubai’s free zones “generated a combined total of US$118 billion in trade value in 2017. The Jebel Ali Free Zone (JAFZA)—established in 1985—accounts for almost 32 percent of the total foreign direct investment flowing into the UAE and for roughly 24 percent of Dubai’s annual gross domestic product.” In 2019, JAFZA reportedly accounted for 70 percent of all trade value. Yet, in data submitted by the UAE authorities to the FATF mutual evaluation team (see Table 2), the requests for financial intelligence from within the commercial free zones remain negligible with only 28 requests made in 2018, and across a period of five years only 99 requests were made.

Table 2: Financial Intelligence Requests from Federal, Dubai and Ras Al Khaimah Public Prosecutions for Money Laundering Investigations

Source: FATF – United Arab Emirates Mutual Evaluation Report (2020).

Once again, the way in which this data is coded and arranged is problematic. In Table 2, reproduced from the FATF report, free zone data is recorded as coming from the commercial free zones, and any data from the financial free zones is lumped together with entities on the mainland and simply categorized as ‘Financial Institutions’ making it difficult to ascertain the supervisory culture and money laundering risks within the free zones. Given the size, scale and importance of the UAE’s free zones to its economy, these low numbers tell an important tale about the lack of enforcement incentive within the UAE. All of this lends credence to the analysis within Chapter 3 that the free zone authorities are primarily motivated by goals of ‘trade facilitation,’ as opposed to ‘trade integrity,’ that is, international trade transactions that are legal, properly priced and transparent.

Finally, the FATF report acknowledged a “wide divergence across the UAE registries as to how adequate, accurate and current beneficial ownership information is maintained,”. However, the report made no mention of the multiple definitions of beneficial ownership in use within some free zones and the absence of any requirements on ownership disclosure for entities registered within the JAFZA. The problems associated with beneficial ownership within the free zones is particularly noteworthy, because of the 4,968 company and trust service providers registered within the UAE, only 717 of which are located on the mainland. This means that the majority of companies registered within the UAE are all based out of free zones, thus exposing the fractured bedrock of the UAE’s financial architecture.

The findings in Chapter 3 and the analysis here do not seek to make the argument that free zones are intrinsically bad and that countries with free zones or free ports are inherently trying to encourage or foster illicit/criminal activity within their territories. The chapter also does not address the efficacy of free zones as a matter of trade and investment policy. Questions around the efficacy of free zones still remain and do need to be thoroughly examined, as the numbers of free zones, or some variant continue to mushroom globally. What is true, however, is that the UAE and Dubai serve as an important and integral hub for legitimate financial and trading activity providing access to markets in the MENA region, Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Therefore, it is clear that the economic incentives of free zones must be counter-balanced against their money laundering and terrorist financing risks, and that supervision and oversight must be an integral part of trade facilitation.

The UAE has the resources to build technical capacity, what is urgently needed is greater political will to bring about changes within its free zones.