By Ijeoma Nwala During his presidential campaign in 2015, President Muhammadu Buhari promised to end all forms of corruption in Nigeria. His anti-corruption fight has received both praise from international governments, like the United Kingdom, which pledged...

By Lionel Bassega, July 6, 2020

Over the last couple of weeks, the rate of Covid-19 infections has flattened in most of the Global North, while the opposite has happened in the Global South. Indeed, according to data from the World Health Organization...

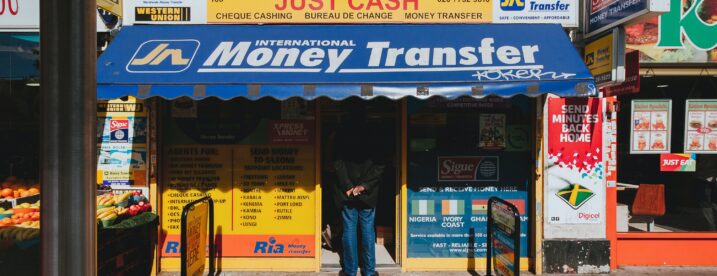

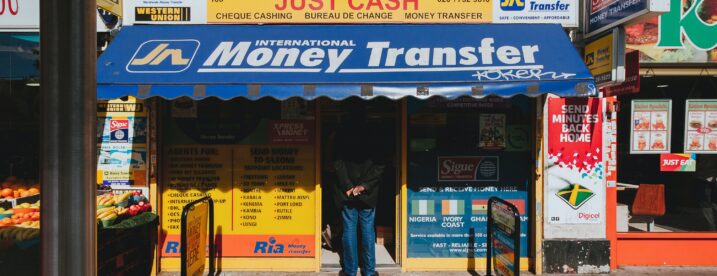

By Julia Yansura and Laura Porras Today, June 16th marks the International Day of Family Remittances, dedicated to recognizing the contributions of the international migrants who send over US$550 billion home to developing countries each year. And...

Nigeria Trade Misinvoicing Leads to Significant Revenue Losses Misinvoicing of Imports and Exports is 15 percent of all Trade Transactions WASHINGTON, DC – Analysis of trade misinvoicing in Nigeria in 2014 shows that the...

By Michele Fletcher, June 11, 2014

Boko Haram developed from social unrest, poverty, and a strong disillusionment with the corruption of the Nigerian government. Today, the same factors make Boko Haram lethal.

Nigeria’s rampant corruption has left the nation unequipped to deal with security concerns, especially along porous borders through which Boko Haram receives immense support. A look at one of their videos reveals an immense amount of weaponry that is not only costly, but very difficult to obtain.

Boko Haram is capitalizing on the destitute and weak areas in the north of Nigeria to extract money from civilians, as well as financial opacity to receive funding from international criminal networks, and channel it towards arms acquisition from abroad: one of many examples of the inextricable link between financial concerns and national security.

By Tom Cardamone, May 28, 2014

A Quarterly Newsletter on the Work of Global Financial Integrity from January through May 2014

Global Financial Integrity is pleased to present GFI Engages, a quarterly newsletter created to highlight events at GFI and in the world of illicit financial flows. We look forward to keeping you updated on our research, advocacy, high level engagement, and media presence.

This year has been busy so far, with GFI staff traveling to six continents within the first three months alone. The following items represent just a fraction of what GFI has been up to, so make sure to check our new website for frequent updates.

Measurable Change in India

In late April, the Indian Directorate of Revenue Intelligence released a summary of its first two years of increased law enforcement activity targeted at cases of commercial fraud, including illicit financial flows through trade misinvoicing. Their early results have been remarkable: between March 2012 and March 2014, they detected $1.3 billion worth of commercial fraud, and collected $396 million in new revenue.

India is just beginning its effort to crack down on trade-related illicit financial flows, and should serve as an example of the potential that curtailing trade misinvoicing has for development. India began working in earnest to reduce illicit financial flows after a report by Global Financial Integrity showed the economy had lost $462 billion since 1948 due to illicit outflows. Following years of intense political debate and public outcry, the Indian Ministry of Finance declared trade misinvoicing its ‘top priority’ and began working with GFI and others to address it.

For most of my professional life, I owned and operated a number of businesses in Nigeria. My partners and I would find a failing company, buy it out, and rebuild it as an efficient, well-run enterprise that turned a profit. We paid our taxes, refused to participate in bribery or corruption, and created jobs.

I am sad to say that when Nigerians look into the future, they do not see the optimism that I experienced back in the 1960s and ’70s. Their country has been torn apart not just by civil war, but also by the terrible forces of crime, corruption, and tax evasion. After years of seeing the quality of life for so many people in Nigeria decrease, I decided that I was obligated to do something about it. I founded Global Financial integrity, an organization dedicated to curtailing illicit money leaving countries like Nigeria around the world.

In 1961 I arrived in Lagos, Nigeria, to take over the management of a company. One of the early conversations I had was with an “old coaster,” a British gentleman who was managing director of a UK-based trading company that had been active along the west coast of Africa since the late 1800s. I asked him, “How do you do business in Africa?” He looked me skeptically up one side and down the other and wasn’t very forthcoming. I got the distinct impression that he did not like Americans showing up in his former British colony so soon after independence. But I pressed on as is my American manner and asked further, “Well, okay, tell me, how do you price your imported cars and textiles and building materials to sell in the Nigerian market?” He answered, “Price? Price is not a problem. I’m not trying to make a profit.”

Imagine my surprise. I had just finished Harvard Business School learning all about how to make a profit and here in Africa one of the first persons I encounter tells me he’s not trying to make a profit. What could be going on here?