South Africa, Revisited: Trade Misinvoicing and Lost Revenue in 2016

August 29, 2019

by Ben Iorio

In November 2018, Global Financial Integrity published an analysis of South Africa’s potential revenue losses associated with trade misinvoicing, finding losses of approximately US$37 billion in revenue, or on average $7.4 billion between 2010-2014. Trade misinvoicing occurs when companies or individuals falsify the prices of goods on import or export invoices in order to avoid import taxes or qualify for subsidies, respectively. Trade misinvoicing is also a common method of illicitly shifting money in or out of countries and constitutes a major form of illicit financial flows (IFFs), resulting in a massive loss of tax revenues for developing countries.

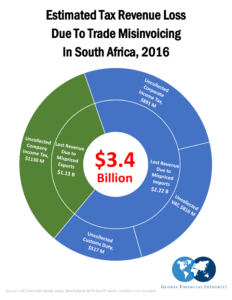

Using newly released data from the United Nations Comtrade database, we estimate South Africa lost approximately $3.4 billion in tax revenues to trade misinvoicing in 2016, or about 4.0 percent of total South African tax revenues collected that year.

GFI also examined how this lost revenue has impacted South Africa’s efforts towards achieving the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Trade Misinvoicing

Individuals and companies engage in trade misinvoicing in order to avoid customs duty and value-added taxes (VATs), to claim government subsidies, or as a way to launder or send illicit money overseas.

Using our “value gap” analysis, we examined the differences between what South Africa and its trading partners both reported as having imported/exported to each other within a given year, allowing us to identify four major types of trade misinvoicing, as described in the table below:

Trade misinvoicing occurs in four main ways: import over-invoicing, export under-invoicing, import under-invoicing, and export over-invoicing. For example, if China reported a shipment of $3 million worth of machinery exported to South Africa in 2016, but South Africa only reported $2 million worth of machinery imported from China that year, then either the exporter on the Chinese side has committed export over-invoicing, or the importer on the South African side has engaged in import under-invoicing.

This method of illicitly shifting money in and out of countries decreases government revenue, leading to a direct drop in public investment and undermines government efforts to increase spending on developmental goals.

South Africa, 2010-2014

The 2018 report examined South Africa’s bilateral trade statistics as reported to UN Comtrade to estimate the level of trade misinvoicing that occurred between 2010-2014. GFI then used South Africa’s prevailing VAT tax rates, corporate income tax rates, customs duties and tax rates on royalties to estimate annual revenues losses of approximately $7.4 billion, or $37 billion over the five-year period.

Such a drastic loss in revenue directly translates into real social costs, as tax evasion on this level exacerbates inequalities, contributes to poverty and insecurity and undermines national efforts to promote sustainable economic growth. The estimated $37 billion in lost tax revenue likely reduced South African development spending between 2010 and 2014.

South Africa, Revisited

For 2016, we estimate South Africa lost approximately $3.4 billion in tax revenues to trade misinvoicing, or about 4.0 percent of total tax revenues collected in South Africa in the same year.

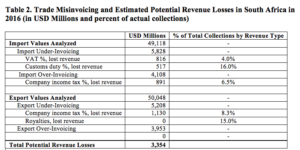

Using our value gap analysis (see GFI’s Methodology for further details), we analyzed approximately $49.1 billion of South Africa’s imports and $50 billion in exports, comparing the South African records with its trading partner records for 2016. We identified approximately $9.9 billion in misinvoiced imports and $9.2 billion in misinvoiced exports. Additionally, we identified approximately $2.2 billion in revenue losses to import misinvoicing and $1.1 billion in revenue losses to export misinvoicing for a total estimated revenue loss of $3.354 billion in 2016. The results are presented below in Table 2:

South Africa & the SDGs

Such extreme losses of tax revenue have a negative impact on South African financing for the SDGs. According to South Africa’s National Development Plan (which is closely aligned with the international SDGs), the country aims to eliminate poverty and inequality by 2030. The 2019 South African Voluntary National Review, used to track current SDG progress, noted that while considerable progress has been achieved on goals related to gender equality, climate control and urban development, South Africa is still not making enough progress on other indicators, particularly efforts to reduce inequality (SDG 10), discrimination and violence against women (SDG 5) and efforts to reduce carbon emissions (SDG 7 and SDG 13). Our analysis suggests South Africa could have realized greater degrees of progress on the SDGs, had it not lost $3.4 billion to trade misinvoicing in 2016.

For example, according to the NGO Government Spending Watch, in 2016 South Africa spent approximately $17.8 billion (ZAR 259.6 billion) on education, $611.3 million (ZAR 8.91 billion) on the environment, $10.7 billion (ZAR 155.4 billion) on health and $10.5 billion (ZAR 152.4 billion) on social protection (poverty, unemployment and housing).

If South Africa had spent an additional $3.4 billion on development in the same proportions as above, it would have resulted in an extra $1.5 billion in spending for education (SDG4), $50 million for the environment (SDGs 7, 13, 14 and 15), $904 million for health (SDG 3) and $887 million for social protection (SDGs 1, 5, 8 and 11). This additional spending could have enabled greater progress towards achieving goals in equality, reducing violence against women and decreasing carbon emissions.

Of course, South Africa might well have spent the lost $3.4 billion on other items in its national budget, but this exercise serves to illustrate the point that unchecked trade misinvoicing can result in significant social costs and undermine ongoing efforts to achieve national development goals.

GFI’s Policy Recommendations for South Africa

We recommend three critical ways South Africa can curtail revenue losses associated with trade misinvoicing: 1) Pass legislative and regulatory measures to reduce trade misinvoicing; 2) take administrative steps to better detect trade misinvoicing (such as using tools like GFI’s GFTrade, which tracks recent trade prices across major trading countries in real time); and 3) take corrective steps to claw back lost revenue via subsequent audits and reviews.

Additionally, South Africa could also: 1) pass “beneficial ownership” legislation that identifies the owners of companies to authorities and to use its diplomatic clout to encourage all other countries to do so as well; 2) encourage all governments to adopt and fully implement the anti-money laundering regulations promoted by the Financial Action Task Force; 3) encourage other governments to adopt the implementation of country-by-country reporting; 4) encourage all governments to actively participate in the worldwide movement towards the automatic exchange of tax information; and 5) encourage all governments to sign on to the Addis Tax Initiative.

South Africa does not need to lose critical tax revenue to trade misinvoicing every year. If South Africa adopted the recommendations here, it could prevent future revenue losses and greatly increase its domestic spending on national development goals. Additionally, if South Africa encouraged other countries to take similar steps, it could help reduce trade misinvoicing at the global level as well.

Ben Iorio is a student in Economics at the University of Michigan and a GFI 2019 Summer Intern.