The Global Crisis of Corruption

July 13, 2020

By Rick Rowden and Jingran Wang

Corruption is a global scourge. It represents a huge loss to taxpayers and governments around the world struggling to provide adequate services for their citizens. It is particularly damaging in developing countries, where lost tax revenues undermine efforts by governments to progress on the internationally agreed-upon United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as other national economic development priorities and emergencies like the Covid-19 pandemic.

The global focus on anti-corruption efforts – especially in poor countries – is a relatively recent development. It was not until the so-called “Cancer of Corruption” speech in 1996 by then-World Bank President James Wolfensohn that the international lending community uttered the dreaded “c-word” (i.e. corruption) in public. With that, the floodgates opened and billions of dollars have been spent in an effort to help developing country governments address their corruption problems.

However, despite many years of work by donor countries and international institutions to defeat corruption, analysis of leading corruption surveys by Global Financial Integrity (GFI) suggests these efforts have not been particularly successful in curbing corruption.

‘Measuring’ corruption

Despite the pervasiveness of the problem, it is actually very difficult to precisely measure the amount of money lost through corrupt practices each year. While the main international financial institutions (the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund) demur at suggestions to try to establish a baseline figure for “grand corruption” (funds stolen by government officials), a remarkable February 2020 World Bank working paper provided a peek behind the curtain, finding that World Bank aid disbursements to the most aid-dependent countries coincided with significant increases in deposits held in offshore financial centers known for bank secrecy and private wealth management. The amounts of foreign aid that had gone missing “suggest[s] a leakage rate of around 7.5 percent for the average highly aid-dependent country.” The funds stolen from developing country budgets were not included in this estimate.

Transparency International is a leader in assessing perceived levels of corruption across countries with its annual Corruption Perception Index (CPI). The CPI is based on thousands of surveys conducted each year on the perceived degree of corruption in governments, with an annual ranking and scoring system from zero (“highly corrupt”) to 100 (“very clean”).

Likewise, the World Bank’s Control of Corruption Index (CCI) scores (number six within its set of Worldwide Governance Indicators) rank countries according to their perceived levels of corruption. Similar to the CPI, the CCI is based on thousands of surveys conducted each year on the perceived degree of corruption in governments, with an annual ranking and score system from 0 to 1, with higher values corresponding to better outcomes. Despite the subjective limitations of the survey method for ranking government performance, these indices are still considered the best available approximations of shifts in degrees of international corruption in the world from year to year.

Assessing 20 years of anti-corruption data

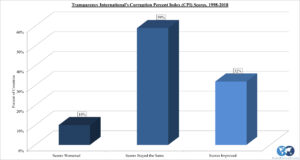

GFI examined 20 years (1998-2018) of CPI country scores, breaking them into five quantiles to determine how many countries’ scores had improved, worsened or stayed roughly the same over the period. Figure 1 shows that of the countries examined in the CPI, ten percent worsened their scores; 59 percent remained relatively unchanged; and only about one third (32 percent) improved their scores over the period. This suggests that, according to the CPI, corruption levels were perceived to have either gotten worse, or stayed the same in nearly two-thirds of the countries examined over the last two decades.

Figure 1. Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) Scores, 1998-2018

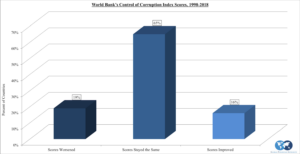

Similarly, GFI examined 20 years of published annual scores on perceived corruption by the World Bank’s CCI scores. Figure 2 shows that of the countries examined, 19 percent worsened their scores; 65 percent kept their scores roughly the same; and only 16 percent of countries saw their scores improve over the period. This suggests that, according the World Bank’s CCI, corruption levels were perceived to have either gotten worse, or stayed the same in nearly 85 percent of the countries examined over the last two decades.

Figure 2. World Bank’s Control of Corruption Index Scores, 1998-2018

As both sets of analysis suggest, international anti-corruption efforts have been lacking in widespread and sustained success. This might have been predicted given that in 2004, eight years after the World Bank initiated its anti-corruption program, an internal assessment noted that while progress had been made, “the Bank has demonstrated only modest success so far in achieving durable outcomes.”

A way forward

However, none of this means that the international community and aid donors should not continue their efforts to stamp out corruption. The kinds of structural and institutional change needed to curtail corruption are the work of generations, and not individuals alone. Phil Mason, a retired Senior Anti-corruption Adviser at the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID), recently reflected on 25 years of anti-corruption efforts by DfID and other bilateral donors and international institutions. He identified some key lessons regarding where the sector has gone wrong, as well as some suggestions on how to think differently about combatting corruption in the future:

- The governments that aid donors and international institutions engage with are “part of the problem, and need to be seen as such. Donors need to stop deluding themselves that their ‘partners’ share an equal ambition to tackle corruption”;

- “Politics” matters. A purely technocratic approach, which donors are most comfortable with, will not succeed;

- There is a need to both repair weak institutional systems and the incentive structures in society. Currently, in many developing countries malfeasance is incentivized over integrity and manifests itself as impunity;

- The interdependencies of institutions – and the need for better coordination among them – matter greatly.

Mason cites 2011 research by Bo Rothstein examining Sweden’s transformation from a corrupt eighteenth century society to the relative “paragon of cleanliness” it is seen as across the Nordic world today. Rothstein’s research points out none of the reforms that were instrumental in changing the social norm away from corruption were actually explicitly targeted against corruption. Rather, the key building blocks seemed to be education, openness of access to public positions and related freedoms in trade, universities and political representation. This same insight was underscored in a similar review of ten country case studies of successful transitions from a corrupt past. All were undertaken for intensely political reasons – and the reduction in corruption came as a by-product.

As the international community faces the raising societal and economic costs of the Covid-19 crisis, it would do well to consider a holistic approach to anti-corruption work, as described above. Indeed, efforts to combat corruption must actually be multiplied during this period, as historically pandemics have presented great opportunities for corruption.

Building on the insights of Mason and Rothstein, GFI believes that there is no one-size-fits-all approach or silver bullet for ending corruption. Nor is there support for the logic sometimes expressed by foreign aid donors that “you have to fix corruption first before doing anything else.” Rather, GFI believes corruption generally flourishes where it is allowed to hide in the shadows, and therefore the best antidote is greater transparency.

Unfortunately, there is still a tremendous amount of secrecy in the world, ranging from government procurement and tax policy, to banking, finance and more. In this regard, GFI is optimistic about the growing number of critical new initiatives underway around the world. Collectively, GFI believes that over time, and with continued citizen engagement, such efforts can help reduce the secrecy that allows corruption to thrive.

Some of the most critical efforts to bring about greater transparency and accountability to citizens, businesses, governments and the media include measures to:

- Conduct automatic exchange of information:

Under conventional practices, national tax authorities of different countries only exchange tax information about specific companies upon request, and sometimes not even then. Governments are increasingly signing on to join the international Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes to establish mechanisms for the automatic exchange of information (AEOI) on taxation data with partner countries. Currently, over 100 countries have signed on to participate in AEOI going forward, but many others, particularly among developing countries, still need to do so.

- Implement beneficial ownership registries:

Although various types of Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) regulations have been adopted by financial institutions of all kinds, it is still very difficult for such organizations to understand and verify exactly who they are doing business with. One of the biggest obstacles is the widespread abuse of complex ownership structures to conceal the identities of “beneficial owners” of companies, which was made clear by both the 2016 Panama Papers and 2017 Paradise Papers, underscoring the complex nature of ownership structures of multinational companies.

Public and international pressure to implement national registers of beneficial ownership information has been gaining in recent years. The UK became one of the first countries to implement a public register back in 2016. Additionally, the European Union recently approved a directive to require EU member-states to create their own registers (albeit private), though implementation has been slow. The US is also currently negotiating beneficial ownership legislation, with a landmark bill passing the House of Representatives in October 2019 and a companion bill due for consideration in the US Senate this year.

- Implement country-by-country reporting:

One of the major obstacles for accurately identifying tax evasion and avoidance by multinational companies is the lack of adequate corporate tax information shared between countries at the international level. The lack of such data prevents tax authorities from carrying out transfer pricing assessments on transactions between linked companies and therefore from carrying out audits. The Organization for Economic Co-operation & Development’s (OECD) Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Action 13 report provides a template for multinational enterprises to report annually to each tax jurisdiction in which they do business. If companies were required to file their tax returns in this way, known as Country-by-Country Reporting (CbCR), governments everywhere, particularly developing countries, would likely see a significant increase in tax revenues.

- Make trade misinvoicing illegal:

One of the largest types of illicit financial flows (IFFs) is wealth that flows illicitly across international borders hidden within the regular commercial trading system. This happens when importers and exporters falsify the invoices they submit to customs authorities by either over-pricing or underpricing their imports and exports. GFI found a value gap of US$817.6 billion in 2017 alone when examining the differences in trade reports between 135 developing countries and 36 advanced economies. The largest hurdle customs agencies face in addressing this problem may be that in many countries falsifying trade invoices is not criminalized. Countries should take steps to adopt legislation clearly criminalizing trade misinvoicing and ensuring adequate associated penalties.

- Implement trade misinvoicing risk assessment tools:

Governments should consider adopting price-filter tools that help customs officials identify potential trade misinvoicing in international trade. When importers and exporters submit invoices with a stated value for their cargo, customs officials should be able to check those values to determine if they are consistent with recent average international prices as a way to detect potential trade misinvoicing. If the declared price on an invoice is significantly different from the comparable average prices prevailing over the previous 12 months on world markets, the cargo could be flagged for further investigation. Along similar lines, there are important efforts underway to explore how distributed ledger (blockchain) technology can be used to identify trade misinvoicing.

- Establish multi-agency teams to address customs fraud, tax evasion and other financial crimes:

One important problem that undermines efforts to combat corruption is that various government agencies, financial investigation units and law enforcement agencies tend to not share information or coordinate their efforts well. The OECD, World Bank and other institutions have advocated for governments to take a collaborative approach to fighting financial crimes. This would require eliminating silos between relevant agencies (ex. customs, financial intelligence units, revenue authority, and law enforcement among others). Enhanced cooperation, information sharing, and interdiction strategies are among the critical steps needed to foster an effective centralized approach to curtail corruption.

- Strengthen customs oversight of free trade zones:

Currently, there is a major problem with a lack of regulatory oversight of the activities within the world’s free trade zones (FTZs). Governments should consider adopting the World Custom Organization’s (WCO) voluntary SAFE Framework of Standards to Secure and Facilitate Global Trade in FTZs, including a set of global recommendations designed to strengthen the effectiveness of customs controls in the zones. As of November 2019, 171 states had signaled their intention to apply the SAFE Framework, but the degree of actual implementation remains unclear.

- Closing offshore centers and tax havens that act as “secrecy jurisdictions”:

Without access to the international financial system, corrupt public officials throughout the world would not be able to launder and hide the proceeds of looted state assets. Major financial centers urgently need to put in place mechanisms to stop their banks and cooperating offshore financial centers from absorbing illicit flows of money. Revelations such as the 2020 Luanda Leaks underscore the importance of offshore centers and tax havens in aiding and abetting global corruption. Public pressure needs to be coordinated on an international level to pressure governments into closing down such places as a necessary cornerstone of the global effort to reduce corruption.

- Support freedom of the press:

Press freedom is fundamental to combatting corruption, yet almost half of the world’s population does not have access to freely-reported news and information, with many living under various kinds of censorship. Additionally, every year hundreds of reporters are attacked, imprisoned, or killed – posing a serious obstacle to exposing corruption. This is why efforts to stamp out corruption often go hand in hand with the need to defend the right of journalists to report the news. This is particularly true for investigative journalists who often take great risks to expose financial corruption, for example, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, and many others.

- Support freedom of information:

Freedom of information legislation is an important tool for holding governments to account, as it requires them to be more transparent in their activities, especially how they spend public finances. In this regard, the global movement for expanding national and local budget-tracking initiatives is an incredibly important development. This not only essential for the fight against corruption, but it helps build stable and resilient democracies. Additionally, improved access to information tends to generally increase the responsiveness of government bodies, while simultaneously having a positive effect on the levels of public participation in a country. The protection of whistleblowers is also crucially important. Over the past 15 years, global progress on access to information, both in law and practice, has been significant. Nearly 120 countries around the world have adopted comprehensive freedom of information laws, encompassing nearly 90 percent of the world’s population. However, there remains a long way to go to instill genuine transparency and protect the right to information for all.

- End impunity

There must also be demand for law enforcement and national courts to end impunity. Public pressure demanding increasing effectiveness from law enforcement is critical to ensuring the corrupt are punished and the cycle of impunity is broken. Nothing is more corrosive to anti-corruption efforts than seeing corruption go unpunished. Civil society can support the process with initiatives such as Transparency International’s Unmask the Corrupt campaign and supporting organizations like World Justice Project.

The global effort to reduce corruption is dependent upon all of these interlocking steps to realize greater financial and information transparency. Crucially, realizing such transparency requires high levels of citizen engagement and ratcheting of public pressure for meaningful improvements on a number of fronts over time at the national and international levels. Fighting entrenched corruption is work that will take decades, but the dividends are likely to pay out long afterwards.

Jingran Wang is a GFI Spring 2020 intern.