Corruption and Money Laundering in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Tale of Two Indices

By Leon Dawson, June 12, 2025

The Latin American and Caribbean countries that experience high levels of corruption can be ideal for laundering criminal proceeds. In a general manner, corruption erodes governance and institutions enabling weak oversight mechanisms for preventing and countering financial crimes. Furthermore, it promotes illicit financial flows to enter the financial system and degrades sectors of the economy, making an ideal ecosystem for laundering money and assets. Two indexes will be analyzed in this blog post with conclusions on how countries perceived as highly corrupt are most of the time considered at high risk of money laundering (ML).

The Corruption Perception Index (CPI) from Transparency International indicates how a lack of transparency and accountability directly impacts countries from Latin America and the Caribbean in the violation of human rights and the increase of the influence of the elite and organised crime on policy-making. The methodology used by the CPI is developed by the selection of 13 different sources, counting institutions that have captured the perceptions of corruption in the past two years, then a standardization procedure takes place by subtracting the mean of each source in the baseline year from each country score, then dividing the standard deviation of that source in the baseline year, for that reason can be compared year on year.

On the other hand, the Basel Institute anti-money laundering (AML) index, whose methodology is based on topics and data sources like reports of AML such as the mutual evaluations from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), corruption and fraud frameworks like the CPI or the Global Organized Crime Index, financial and public transparency with sources from the Tax Justice Network and the World Bank; and finally the political and legal risks, with reports from the World Justice Project or the Freedom House.

Corruption vs. money laundering in Latin America and the Caribbean

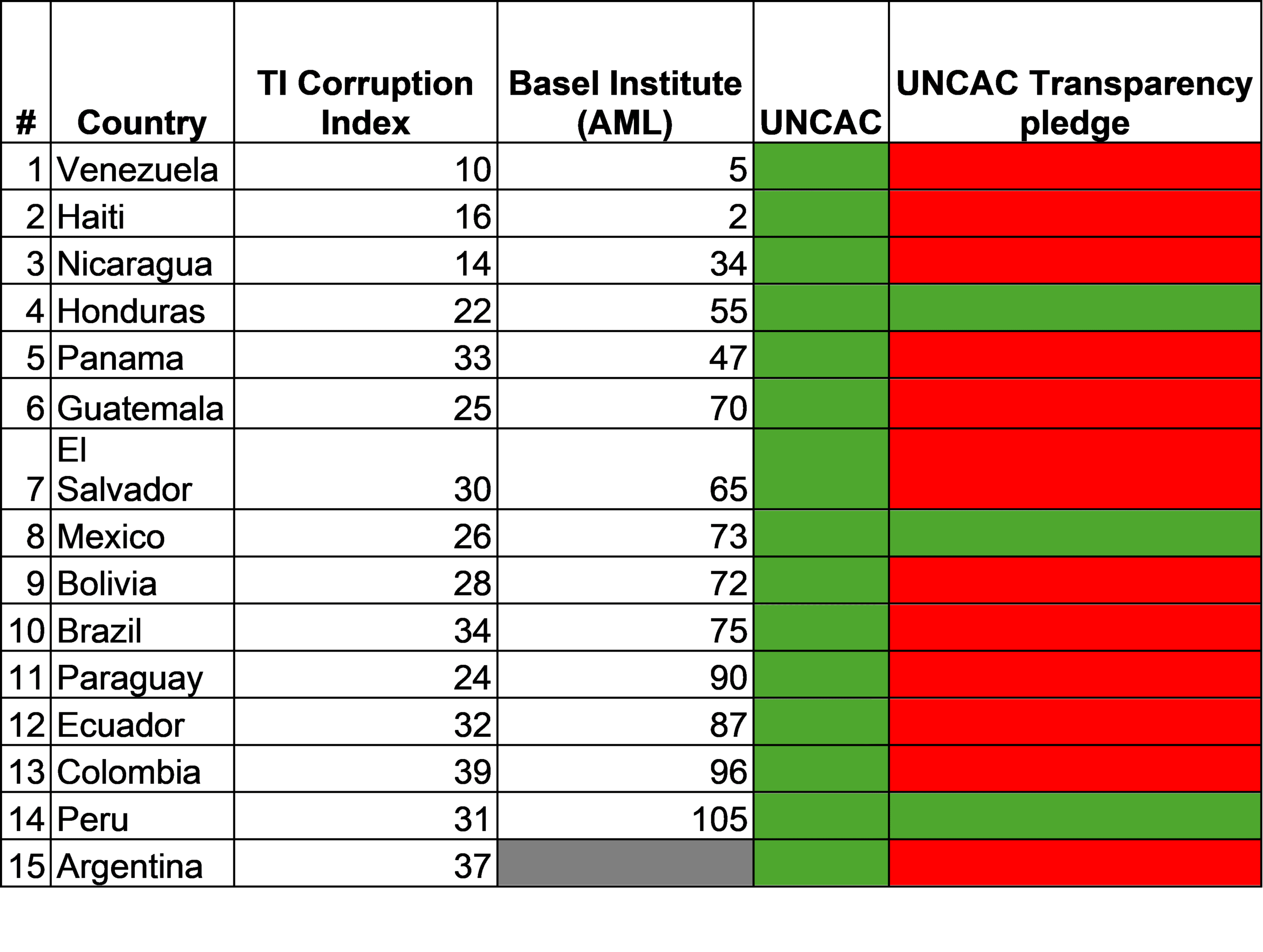

Data taken from the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index, the Basel Institute Anti-Money Laundering Index, the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) and the UNCAC transparency pledge.

Data taken from the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index, the Basel Institute Anti-Money Laundering Index, the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) and the UNCAC transparency pledge.

Of 90 countries in the CPI, 33 countries represent non-democratic regimes, where at least 15 countries from the Latin American and Caribbean region in 2024 were perceived as highly corrupt. This includes some Central American countries like Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala; South American countries like Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador and Caribbean countries like Haiti, Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica, among others in each region. Some of these countries are also ranked in the AML Risks and Financial Crimes Index as high risk.

The data extracted from the Transparency International CPI and Basel Institute AML Index might suggest a strong relationship between corruption and money laundering risks in LAC. Countries with high levels of perceived corruption tend to also rank poorly in money laundering risk assessments. For example:

- Venezuela, Haiti, and Nicaragua have some of the worst corruption scores in the region (CPI scores of 10, 16, and 14, respectively). These same countries rank highly on the Basel AML Index, indicating significant vulnerabilities in their financial systems to illicit financial flows and financial crime.

- Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico show a similar pattern, where weak governance structures and high corruption levels align with elevated AML risk scores.

Conversely, some countries, such as Argentina and Brazil, have relatively better CPI rankings but still face high ML risks, demonstrating that AML vulnerabilities extend beyond traditional corruption concerns to include regulatory and institutional weaknesses.

Another major trend seen in the CPI and Basel AML Index is that countries with weak democratic institutions and fragile rule of law tend to have higher risks of corruption and money laundering. This can be attributed to:

- Corruption erodes law enforcement, judicial independence, and regulatory agencies, making it easier for illicit financial flows to circulate undetected.

- Countries where organized crime and political elites influence financial regulation tend to have higher AML risks.

- Even where AML frameworks exist, a lack of effective enforcement weakens their impact.

For example, Paraguay, Ecuador, and Peru exhibit relatively moderate corruption scores compared to the worst performers, yet their AML risk scores remain high (90, 87, and 105, respectively). This suggests that, beyond corruption, other factors such as regulatory loopholes, tax havens, and weak FIUs might contribute to money laundering risk.

As for the Caribbean, it is often associated with low-tax jurisdictions, The AML Index reveals that several Caribbean nations face serious money laundering risks, despite having mixed corruption perceptions scores. Some key insights include:

- Panama (CPI 33, AML Risk 47) – Despite ongoing reforms, ML vulnerabilities through offshore entities and shell companies might persist.

- Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago have faced growing scrutiny due to concerns over drug trafficking-related financial crime.

- The Bahamas and the Cayman Islands, though not explicitly covered in the dataset, have been subject to FATF graylisting in the past.

This underscores a critical issue: even countries with moderate corruption levels can still present high ML risks due to financial secrecy laws, lack of transparency in beneficial ownership registries, and gaps in AML enforcement.

Opportunities and Challenges

The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) plays an important role and represents an opportunity in the anti-corruption system framework of these countries because it promotes standardization of preventive measures, which involves not only the conduct of public officials or the private sector, but also the role of civil society towards awareness of corruption. The Latin American and Caribbean countries mentioned on those indexes have ratified the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC); moreover, on the promotion and strengthening measures for countering corruption, the asset recovery process represents an opportunity within’s UNCAC framework for these countries to return the assets to the public administration.

Measures such as gathering evidence and asset detection, beneficial ownership of those assets, national and international coordination and cooperation, seizure and finally the return of these assets, can represent a challenge for law enforcement agencies countering corruption because those investigations need independence, international cooperation and capacity building towards new forms on obfuscating the origin of the funds. For example, when these assets are laundered through the traditional financial system and cryptocurrencies, it makes it more complex.

Another challenge is the enforcement of the UNCAC, which has developed mechanisms for reviewing its application, through a transparency pledge that has only been implemented by Chile, Peru, Guatemala, and Honduras within the Latin American region.

Recommendations

Some of the recommendations that can be addressed to countering corruption and preventing money laundering as a consequence are the following:

- For the public sector, it is important to develop a multisectoral approach among national and international agencies in order to exchange relevant information for the implementation of strategies, with the purpose of preventing and mitigating financial crimes such as money laundering as a consequence of corruption.

- The private sector’s role in preventing corruption can be initiated by capacity-building programs for its staff. Awareness at all company levels of how corruption negatively impacts their business is a key pillar for corporate transparency.

- Investigations in corruption cases should consider the participation of independent investigators who can avoid a possible conflict of interest within the public administration.

- The role of civil society is crucial for transparency and accountability, as UNCAC emphasises its importance, governments should implement mechanisms of participation like discussing decision-making in public policies and the elaboration of new legal frameworks.

*This report was written with the support of Claudia Marcela Hernández, program manager LAC

Photo: Global Financial Integrity