The Odebrecht Case: The role of social mobilization and journalism

June 25, 2019

By Diana Pérez Córdova

There is nothing more inspirational than to see a country come together to accomplish a common goal. Time and time again, thousands of people have gathered together to exercise their right to demonstrate, evidencing that the power conferred on politicians is not something to be taken for granted or abused.

A great example of this today are the inspirational marches that have flooded the streets of various Latin American countries in response to one of the most outrageous cases of corruption in the modern age: the Odebrecht case. In cities across Peru, Colombia and the Dominican Republic, people took to the streets to demand accountability from the politicians accused of corruption. A key component in mobilizing these protests has been the work of the journalists who uncovered the alleged misdeeds of the corrupted institutions and individuals.

The Odebrecht Case

Odebrecht is one of the most important construction companies in Latin America, with operations in 13 countries across the region, as well as Europe, Africa and the Middle East. In Latin America, the company had acquired contracts for public construction with the governments of Argentina, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Dominican Republic and Venezuela. However, in 2014, a Brazilian investigation nicknamed Lava Jato (Car Wash) uncovered a network of bribes between politicians and private companies that included Odebrecht.

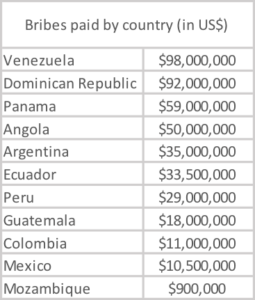

From that investigation, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) launched an investigation in 2016 uncovering a system of bribes Odebrecht paid to different governments in Latin America for the acquisition of public construction contracts. The DOJ considers this case to be the “largest foreign bribery case in history”, not only because Odebrecht paid approximately US$788 million in bribes, but also because of the intricate network through which the payments were made. The countries affected are still in the process of disentangling the twisted web of various companies, shell companies, businessmen and politicians. The amounts of bribes distributed across Latin American and a few African countries is as follows:

Source: Odebrecht Information Report (DOJ)

(A June 25, 2019 investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the Miami Herald has revealed that “Odebrecht’s cash-for-contracts operation was even bigger than the company has acknowledged, and involved prominent figures and massive public works projects not mentioned in the criminal cases or other official inquiries to date.”)

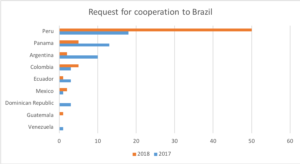

Brazilian authorities have shown a great willingness to share documents, declarations and general information with all of the affected countries. In that regard, Brazil has published data regarding the quantity of information requests it has received from other countries, which serves as an indication of a country’s progress and general interest in investigating:

Visualized by: GFI / Source: JOTA and Transparency International

Despite the overwhelming information collected by Brazilian and American authorities, not all countries have made the same level of progress in their investigations. Peru has made the most information requests (68), as well as the most progress in their internal investigation and prosecution of the case. Colombia received less in bribes than Peru ($11 million vs. $29 million), but proportionately, the cooperation requests (8) have been limited, as is the extent of their investigation. The Dominican Republic, despite being one of the top receivers of bribes ($92 million), has sent the least requests for cooperation (3).

In these three cases, social mobilization has been the main determinant of how large or limited the actions by the prosecution have been. Furthermore, the work performed by journalists in each country demonstrates the differences in the capacity of each anti-corruption mobilization to pressure authorities to enforce justice.

Social Mobilization and Journalism

Peru

When the Odebrecht case reached Peru, political parties and politicians were quick to condemn the case and promptly deny any kind of link to the company. The government of Peru and its institutions vowed to investigate and find those immersed in the illicit activity. However, after revelations from key actors inside Odebrecht, only minor agents were prosecuted; for example, those who were in charge of the bidding process, or politicians in specific regions of Peru. Meanwhile, no major government representative or powerful politician has come close to being investigated.

This changed in July 2018, when an independent journal (IDL Reporteros) published audio recordings evidencing collusion between the main political parties and heads of judicial institutions to prevent high level figures from being investigated. These recordings also exposed a system of bribes that the Peruvian judiciary system sold to the highest bidder, or to the person with the best connections in some cases. This triggered outrage among Peruvian people, who went to the streets to demand accountability and the end of impunity. As more and more information was brought forward by journalists, the anti-corruption mobilization increased in numbers and power. As a consequence, the country approved a reform of the judicial system, triggering investigations into some of the most influential political parties and their representatives in Peru. Furthermore, the heads of five most notorious political parties are currently either in jail or on the run (former Peruvian president Alan García committed suicide moments prior to being detained in April 2019).

This series of events demonstrates that Peruvian people are no longer resigned to a politics of corruption. They have become strong critics of the political actions of the government with respect to addressing corruption. This social awareness has been crucial to securing the independence of the judiciary system in the investigation, as well as weakening the network of corruption in Peruvian governmental institutions.

Colombia

As in Peru, the 2016 DOJ findings that Odebrecht paid $11 million in bribes to Colombian politicians were roundly condemned by the public and all political parties. Colombia requested more information from Brazil and the U.S., and proceeded to investigate some minor politicians while promising an extensive investigation.

However, the investigations have not gone much further, creating a sentiment in Colombia that strong corruption in the country is delaying the investigation. This notion was fueled even more so in December 2018 with the death of two key witnesses in the Odebrecht case by suspicious circumstances. The reality is that the investigations have been very limited as they only address some of state contracts with Odebrecht, and few investigations have been carried out examining presidential campaign financing, which was Odebrecht’s preferred method of bribery.

Colombians have protested to demand accountability since the case first broke and the limited investigation that has been performed so far is in response to the pressures derived from the protest, known as the “Lanterns March” (Marcha de las linternas). However, as previously mentioned, the level of impact of the social movement strongly depends on the materialization of information and evidence to pressure the government to hold individuals accountable for their involvement. Journalists are trying to unravel the intricate networks behind this case and the connection between political power and the judicial system, but not much has been accomplished yet.

The risk for Colombia is that people will become fatigued and opt for indifference. If that happens, corruption will have won once again.

Dominican Republic

In the Dominican Republic, there have been few consequences as a result of the Odebrecht case. At one point, the Dominican Republic was the only country in the region without any arrests related to the case. Later, 14 people were arrested, but eight of those prosecutions have recently been put on hold. The response to some of the prosecutor’s requests to audit past contracts has delayed responses and in the end, no conclusive information has been obtained. Many journalists report that the prosecutor’s work is tantamount to façade meant to satisfy public opinion, while leaving uncovered the complete networks of corruption.

Indeed, the investigation seems to have stalled and the attention of the press and society has moved on to other topics. Again, as in the case of Colombia, it is difficult and dangerous to shed light on corrupt connections between politicians and the judicial system. For the Dominican Republic, the probability to uncover and truly understand the connection between political power and judicial system is low, as it is a key method for facilitating corruption, and the reason why Odebrecht was able to operate so outrageously for so many years.

In response to this case, a social mobilization called the “Green March” (Marcha Verde) was created to pressure the investigation, but it seems time is running out on people’s interest and participation, making it plausible that those involved will retain impunity.

Conclusion

The only hope for preventing future cases like Odebrecht is for the public to not turn their backs on what is happening. Despite the fact that Odebrecht has perpetrated massive injury upon the region, it could also become an opportunity for each country to investigate their political and judicial systems for corruption. There is an overwhelming amount of evidence to aid investigations, but only if there is a political will to reach justice. In order to galvanize that political will, social movements and journalists need to work closely and unceasingly to uncover corruption wherever it may lurk.

Diana Pérez Córdova is a Master of Arts Candidate at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, concentrating in development economics and comparative politics. She is a 2019 GFI Summer Intern.