Value Gap Methodology

Trade misinvoicing is a method of moving money illicitly across borders, which involves the deliberate falsification of the value, volume or quality of an international commercial transaction of goods or services by at least one party to the transaction. This typically occurs when exporters or importers submit false shipment information on customs invoices when shipping exports or receiving imports.

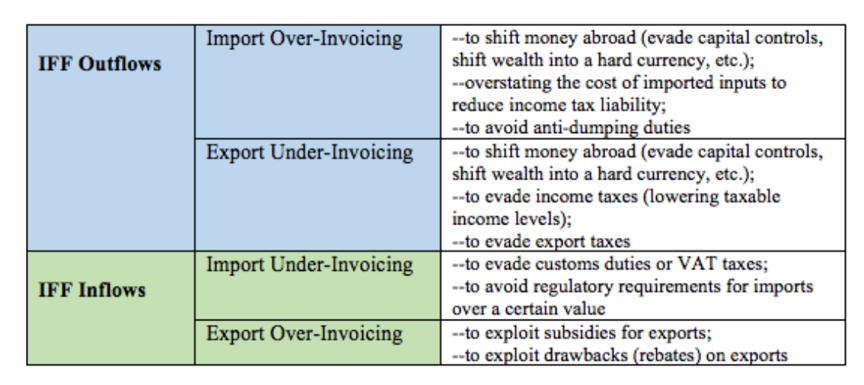

In order to identify a country’s imports/exports that might have been misinvoiced, GFI conducts a “value gap” analysis. In such an analysis, GFI examines a country’s trade with its partners in order to identify four major types of trade misinvoicing. Below, we describe the four main types and common purposes of trade misinvoicing. GFI previously referred to this analysis as a “trade gap” analysis.

As a note, our estimates using this methodology are meant to illustrate the magnitude of the problem. Exact estimates are difficult to make given the quality of the data. Nevertheless, estimates of the value gap due to trade misinvoicing are sufficient for policymakers to grasp the severity of the problem and react accordingly.

These types of trade misinvoicing include two ways of illicitly sending funds into other countries (IFF inflows) and two ways of illicitly sending funds out of a country (IFF outflows). In each case, either method could be used by manipulating the stated prices for goods on invoices of either imports or exports. Each of these four pathways is described below:

Import over-invoicing is done for the purpose of shifting money abroad. For example, instead of paying US$100 per unit for goods, an importer can submit a falsified invoice to read $120 per unit. Upon receiving payment, the exporter transfers the extra $20 into a foreign bank account controlled by the importer. Therefore, while the importer actually pays $100 per unit for the goods, the falsified invoice enables the outflow of $20 per unit into an offshore account. Import over-invoicing is a common method of illegally moving money out of developing countries and results in illicit outflows of funds from a country. There are many reasons why people seek to move money out of developing countries. GFI believes the most common reasons is to shift wealth from countries with weak currencies (whose value often fluctuates and depreciates on world markets) into hard currencies like US dollars, British pounds or EU euros (whose value is more steadily retained). Simple tax evasion is also a major reason.

Similarly, export under-invoicing can also be used for shifting money abroad. This type of trade misinvoicing is done by exporters who are attempting to pay a lower tax on exports and/or is used by companies as an accounting maneuver to officially lower apparent profits and thus, to pay a lower corporate income tax rate. This practice often plagues high-value natural resource exports from African countries. The High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa found that IFFs are most evident in Africa’s resource-exporting countries. Therefore, the use of export under-invoicing also results in illicit outflows of money from developing countries, while also denying export and income taxes owed to the government. Other purposes for export under-invoicing include evading the payment of export taxes and lowering the levels of a company’s taxable income. In this method, the invoice is falsified to show that the price of goods being exported is lower than the actual price being paid by an importer abroad.

Trade misinvoicing is also used to bring illicit funds into countries. A key method of illicit inflows includes import under-invoicing. This type of trade misinvoicing is often used for the purpose of evading the payment of customs duties and value-added taxes (VAT) paid on imports. For example, instead of paying $100 per unit, the importer can arrange for the invoice to read $50 per unit and save on the duties and VAT that would have been payable at the higher unit price. Upon paying the invoice at $50, the importer still owes the remaining $50 to the original producer abroad and therefore must also have a separate means of shifting money abroad in order to complete the transaction. In other words, import under-invoicing is sometimes done with an additional mechanism for shifting un-taxed money out of the country to meet the actual balance due. Import under-invoicing is also a common method for evading capital controls (legal limits on how much money can be brought into or taken out of a country). Since more wealth is being imported into a country than is actually being declared, import under-invoicing results in illicit inflows of funds into a country.

Lastly, export over-invoicing is also used to bring illicit funds into countries. In this type of trade misinvoicing, the prices listed on export invoices are falsified to show that exports are priced at higher levels than what importers abroad have invoiced as being paid. While this may result in exporters paying higher amounts of export taxes than are actually due, such tactics are used to benefit companies that are seeking to abuse various government export incentives programs, such as customs duty and VAT tax drawbacks (rebates). In many countries, there are special government programs designed to encourage exports by offering rebates on the duty and VAT for the costs of any imported materials used in the local production of goods before they are exported. Export prices can also be inflated to receive larger export subsidies from the government. While intended to promote exports, these government programs can create incentives for companies to falsify the price of their exports in order to maximize the benefits of rebates or take advantage of export subsidies. In such cases, companies can earn more through receiving such government rebates and subsidies than they pay in additional (inflated) export taxes. As this results in more money coming into an economy than is supposed to (if exports have been priced accurately), export over-invoicing also results in illicit inflows of funds into a country.

In summary, there are four standard types of trade misinvoicing: under-invoicing and over-invoicing of both exports and imports. Two of these types of trade misinvoicing result in illicit outflows of money out of an economy and two result in illicit inflows of money into an economy. Common reasons for illicit outflows are to evade taxes and shift wealth from weak currencies into hard currencies, while common reasons for illicit inflows are for evading taxes and laundering the proceeds from and/or financing illegal activities of transnational criminal organizations. While much attention is often given to the problem of illicit outflows from developing countries, the problem of illicit inflows is often just as big a problem. In both cases, the result is that taxes are not being paid to governments, resulting in less revenue available for public health, public education and other essential government services.

To undertake a value gap analysis, GFI uses the United Nations Comtrade (Comtrade) database, which each year collects reported data from the majority of countries on their annual imports and exports (In earlier reports, GFI used data from the Direction of Trade Statistics (DOTS) database produced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In our January 2019 multi-country report, “Illicit Financial Flows to and from 148 Developing Countries: 2006-2015,” GFI drew from both the IMF DOTS database as well as the UN Comtrade database. While both databases have strengths and limitations, GFI decided to pull from the UN Comtrade database for this and future reports, primarily because of the scale and depth of the detailed data it provides). To explain this process, we can use GFI’s recent report on trade misinvoicing in Indonesia in 2016. For this analysis, GFI used Comtrade data for Indonesia in 2016 to cross reference Indonesia’s export/import reports against the corresponding reports submitted by all of Indonesia’s trading partners around the world for 2016. In these data sets, we looked for gaps in export and import statistics that are suggestive of trade misinvoicing.

Indonesia reported to UN Comtrade a total value of nearly $135.7 billion in imports and nearly $144.5 billion in exports for a total value of trade of $280.2 billion in 2016. Drawing on this data, GFI then applied a series of treatments to the Comtrade data in order to undertake our value gap analysis. These steps are described in detail in Section IV, “Statistical Treatments of the Comtrade Data.”

After compiling Indonesia’s trade data and that of its trade partners for 2016, we then eliminated three different sets of trade data from consideration. We first eliminated all cases of “orphaned” imports – meaning those records in the database for which Indonesia reported a value for imports of a commodity or good from a particular country while that country reported no exports of that good to Indonesia in that year. Next, we eliminated all cases of “lost” exports – meaning records of exports reported by Indonesia’s trade partners as goods shipped to Indonesia in a particular year, but which were not reported as imported by Indonesia in that year. After eliminating all cases of “orphaned” and “lost” records from the Comtrade data for Indonesia in 2016, we still needed to identify and eliminate a third category of records called “others.” Among the remaining records of “matched values”, i.e., trades for which both Indonesia and its trading partners reported values for that year, “others” are records that do not meet three criteria: 1) non-zero values for the trade must be reported by both the reporting country and its partner; 2) non-zero volumes (quantities) for the trade must be reported by both the reporting country and its partner; and 3) the volumes must be reported in the same physical units of measurement by both the reporting country and its partner. If any of the remaining records of “matched values”, did not comply with all three criteria, these were also eliminated as “others.”

Finally, once all cases of “orphaned”, “lost” and “others” records have been eliminated from the Comtrade data for Indonesia in 2016, and we have applied other technical treatments to the data (described below), we are then left with the remaining sets of “matched” trades to be used in our value gap analysis. GFI has found that, on average between 2000-2015, “orphaned” “lost” and “others” records comprised about 26 percent of all relevant Comtrade records, leaving on average about 74 percent of a country’s Comtrade records available as sets of “matched” trades for use in our value gap analyses.

In our value gap analysis, we identify any gaps found in the reporting data when the reported values by both partners do not match. For example, if Indonesia reported paying $5 million for alarm clocks imported from China in 2016 but China only reported exporting $3 million in alarm clocks to Indonesia in 2016, this would represent a trade gap of $2 million. With Indonesia as the focus country, this would reflect a case of import over-invoicing by Indonesia.

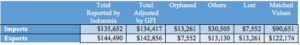

Table 1 shows the results of GFI’s value gap analysis for Indonesia in 2016:

Table 1. Value Gap Analysis for Indonesia in 2016: Identifying Matched Values (in millions of US Dollars)

The figures in column 3 ‘Total Adjusted by GFI’ are somewhat different from the figures officially reported by Indonesia to Comtrade because the data has been treated by GFI in a number of steps detailed in ‘Statistical treatments of the basic Comtrade data’.

Note that the figures representing “lost” exports and “orphaned” imports are mirrored reflections of one another. The “lost” figures are not included in GFI’s analysis because in this case our focus is on Indonesia, and by definition, “lost” refers to goods that officially never arrived, i.e. records of exports reported by Indonesia’s other trade partners as goods shipped to Indonesia, but which were never reported by Indonesia as being imported – so they do not figure into any of Indonesia’s official imports data. In contrast, Indonesia’s “orphaned” imports are records officially reported by Indonesia as imports of goods from other countries, even though those countries did not report them as exports to Indonesia.

The first column shows the values of total imports and exports as officially reported by Indonesia to Comtrade. The second column shows GFI’s adjustments to those values based on a number of treatments of the data that are detailed below in Section IV, “Statistical Treatments of the Comtrade Data.” The third column shows the sum of the values of trade records that were classified as “orphaned”, or those records in the database for which Indonesia reported a value for imports of a commodity from a particular country while that country reported no exports of that good to Indonesia in that year. Because there are no corresponding records for these Indonesian imports from the exporting countries, these records are eliminated from our analysis. The fourth column shows the sum of the values of trade records that were classified as “others”, or those records for which one or both parties to the trade did not report non-zero values, non-zero volumes (quantities), or did not report the volumes in the same physical units of measurement. Again, because there are no corresponding records with trading partners on these three features, these records are eliminated from our analysis. The fifth column shows the sum of the values of trade records that were classified as “lost”, or those records which correspond to shipments reported as exports by Indonesia’s trade partners as shipped to Indonesia in 2016, but which were not recorded as imports by Indonesia in that year. While the “lost” records are included in our initial collection of relevant Comtrade records because they showed up as exports from other countries to Indonesia, they are not included as part of Indonesia’s official trade data for the year, and therefore are also eliminated from our analysis. Finally, after eliminating the “orphaned,” “others” and “lost” records, the sixth column on the far right shows the sum of the values of trade records that were classified as “matched” sets, or those records in the Comtrade database for which both Indonesia and its trading partner countries reported values in 2016. The matched sets are the figures used in GFI’s value gap analysis.

Within Indonesia’s $135.7 billion in imports reported in 2016, we identified sets of matched value trades with its partners valued at $90.7 billion for use in our value gap analysis. Similarly, within Indonesia’s $144.5 billion in exports reported in 2016, we identified sets of matched trades with its partners valued at $122.2 billion for use in our analysis.

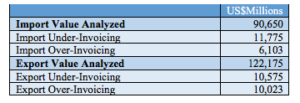

Using the data for the set of matched trades, Table 2 shows the next step in our value gap analysis which identifies the estimated amount of trade misinvoicing for Indonesia in 2016:

Table 2. Value Gap Analysis for Indonesia in 2016: Identifying Trade Misinvoicing Gaps (in millions of US Dollars)

Within the sets of matched trades for Indonesia’s imports, we identified value gaps valued at $17.9 billion. This included cases of import under-invoicing ($11.8 billion) and import over-invoicing ($6.1 billion). Within the sets of matched values for Indonesia’s exports, we identified value gaps valued at $20.6 billion. This included gaps valued at $10.6 billion for export under-invoicing and $10.0 billion for export over-invoicing. Again, these figures represent the estimated value of the gap – or the difference between what was reported to Comtrade by Indonesia and by its trading partners for 2016.

This section describes several limitations of our value gap analysis methodology. Firstly, even after eliminating all cases of “orphaned”, “others” and “lost” records, there are a number of reasons why value gaps may still appear in the Comtrade data for the sets of matched values we use in our analysis. These include: human error; countries that report on the same goods but use somewhat different 6-digit HS product codes for the same products in the Comtrade system; delays in reporting (shipments exported late in one year may not be reported as imports by the partner country until early in the next year); and the problem of re-exports and transit-trade, in which international cargo may temporarily be unloaded from one ship and reloaded onto another ship in one or more countries during the journey from the original exporter country to the final import destination country where consequently, goods can be mistakenly listed as imports to, or exports from, incorrect locations. All of these factors can result in measurement errors and partner misattribution that can undermine the reliability of value gaps as a proxy for misinvoicing.

GFI attempts to mitigate some of these potential distortions in the Comtrade data by applying certain treatments (described in detail below). For example, GFI applies updated data from Switzerland, which prior to 2012 did not report flows of gold and other precious metals in Comtrade data; GFI applies additional data from Hong Kong (a major re-export and transit-trade port) that attempts to clarify the original exporters and final destination importers that transit through Hong Kong as re-exports and which offers a level of detail often not captured in Comtrade data; and GFI attempts to lessen the distortionary impact of reporting errors in the volumes reported for each matched trade by applying a system of weighted measures to the raw trade data that are intended to improve the reliability of the trade misinvoicing estimates. These quality control adjustments work to lower the estimated degree of misinvoicing.

Another factor in prices differences is seen when exporters and importers report a different price for the same good because importers report the actual cost of the good, as well as additional costs for shipping and related transport insurance, known as the cost, insurance and freight (CIF) price, whereas the exporter reports a lower freight-on-board (FOB) price. Therefore, some countries report import values to Comtrade on a CIF basis only, while others report on an FOB basis. Consequently, GFI addresses these price differences by applying a statistical regression that converts all CIF prices to FOB prices for any two countries trading any particular good that can be used for the entire Comtrade database over the 1997-2016 period. In the case of our Indonesia study, this statistical model was applied to all Indonesian import transactions in 2016, adjusting them to an FOB basis.

However, while these various limitations and methodological measurement problems can explain some portion of the identified value gaps, the remaining outstanding gaps are still so considerable in size and scale that GFI concludes that trade misinvoicing continues to be a massive problem. As many of the aspects of trade misinvoicing are by their nature hidden and therefore inherently difficult to measure with precision, GFI remains focused on orders of magnitude. For example, the large scale of the problem was underscored in our January 2019 report, Illicit Financial Flows to and from 148 Developing Countries: 2006-2015, which found that the estimated potential illicit flows in and out of the developing world between 2006 to 2015 amounted to approximately 18 percent of total developing country trade with advanced economies, on average, over the ten-year period (this refers to the analysis undertaken by GFI using UN Comtrade data; See Table II-1 on p.8 of the GFI 2019 report).

Since these estimates are based only on the trade misinvoicing that is able to be detected by its value gap analysis methodology, GFI believes such estimates are very conservative and that the actual scale of illicit financial flows (IFFs) is much larger. This is because there are other aspects of trade misinvoicing that cannot be captured by our value gap analysis and there are a range of other types of IFFs that fall well outside the realm of trade misinvoicing. These other aspects include the following:

Same invoice faking

Our value gap analysis cannot capture incidences of “same invoice faking”, in which both the importer and the exporter have colluded in advance to agree on the prices they will each declare on their respective falsified import and export documents. In such cases, no gap appears between the export and import values and therefore cannot be detected in our gap analysis. This approach is widely used by both multinational corporations and long-term trading partners and is difficult to detect. However – GFTrade – a global trade pricing database tool developed by GFI, enables “same invoice faking” to be detected by contrasting stated prices on invoices against recent average trading prices by all importers and exporters of the same product;

Services and intangibles

Comtrade and other types of available trade pricing data cover only merchandise goods. There is very limited services data for developing countries that is reported to Comtrade. Therefore, even as trade in services as a percent of total world trade has been increasing, a range of misinvoicing in trade in services cannot be detected in our trade gap analysis using Comtrade data. Such trade misinvoicing in services includes falsified invoices for management fees, interest payments, licenses, etc., which have become commonly used avenues for overcharges as a way to shift money out of emerging market and developing countries. An additional factor is that the pricing of services is far more subjective than the pricing of commodities, which have generally clear input costs, etc.;

Cash transactions

Sometimes used in commerce and often used in criminal transactions, cash transactions and bulk cash smuggling do not show up in the official trade data and subsequently cannot be captured in our trade gap analyses. Our value gap analyses cannot detect transactions that utilize mechanisms which avoid the immediate movement of payment, such as hawala and flying money transactions. These techniques are being increasingly leveraged as commerce becomes more internationalized.

While the precise value of IFFs may not be known, the associated lost tax revenues represent a major leakage of public resources that could have otherwise been used for development purposes. For example, in our 2019 Indonesia report, we estimate revenue losses of $6.5 billion to trade misinvoicing in 2016 alone. Such losses of tax revenue undermine efforts by countries to mobilize domestic resources in accordance with their commitments under the internationally-agreed-upon Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 16.4.1., which calls for countries to “significantly reduce value of inward and outward illicit financial flows.”

As mentioned above, gaps can arise in bilateral trade data for a variety of reasons, many of them reflecting legitimate factors. GFI has attempted to address as many such factors as possible, given the limitations of available data. In this section, these adjustments and treatments to the data are summarized.

Swiss gold trade

Asymmetries in the types of trade that countries report can give rise to trade gaps that are unduly large, not because of trade misinvoicing, but because one country may be reporting trade in goods that its partner country does not report. Such was the case with Switzerland’s policy to not report its exports and imports of gold on a bilateral basis dating back to the early 1980s. As a result, it would be the case that some countries (such as Indonesia) would report imports of gold from Switzerland, even as Switzerland reported no gold exports to those other countries (in effect, Swiss gold would be an “orphaned” import for those countries). However, because Switzerland resumed reporting its gold trade on a bilateral basis beginning in 2012, the newer Comtrade data no longer reflect the distortions. For prior years, however, they remain. To mitigate the remaining distortions, GFI adjusted the bilateral trade data in Comtrade using gold trade data published by Switzerland in recent years;

Hong Kong re-exports

Over time, trading hubs for in-transit trade and re-exports have become increasingly important in international trade, displacing the older direct point-to-point arrangements between trade partners. This is because it is more cost efficient for shipping lines to unload and reload goods onto different ships during different legs of a journey than it is to use the same ship for the entire route. As the volume and efficiency of trade worldwide has increased in recent decades, transshipments through trading hubs increasingly complicate the measurement of misinvoicing when using the country-partner trade methodology used by GFI. In general, there are insufficient data to completely disentangle the original exporters and ultimate destination countries from the interim trade flows through such hubs. However, in the case of Hong Kong (a major trade hub with nearly all of the country’s exports consisting of re-exports, with much of that from mainland China), data are available. GFI utilized re-export data from the Hong Kong Census Office and implemented these adjustments at the 6-digit level of commodity detail for the period from 2000 through 2016;

Transport margins

As mentioned above, most countries report the value of their imports on a “cost, insurance, and freight” (CIF) basis whereas they report the value of their exports using the “free on board” (FOB) valuation. To enable direct comparisons of import and export values, all import values must first be converted to an FOB basis. GFI implemented these adjustments in two steps: 1) a statistical model linking CIF/FOB margins for any two countries trading any particular good was developed by GFI in the Comtrade database over the 2001-2016 period; and 2) the statistical model was then applied to all Indonesian import transactions, adjusting them to an FOB basis. There has been an enormous amount of research into the nature of transport costs in trade in recent decades and the statistical work performed by GFI, in particular, builds upon the research reported by the Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (CEPII) and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). GFI’s model for converting CIF values into FOB values extends the determinants of transport margins developed by CEPII (namely, the role of such factors as distance between trade partners, contiguity, the degree to which a country is land-locked, and “world” prices for individual commodities) and includes factors such as the presence of trade agreements between partners (which should lower the costs of trade) and categorical factors as to whether either or both trade partners are developing countries (proxies for the quality of a country’s infrastructure), among others. This is a less extensive list of factors than that used by the OECD, but using more elaborate infrastructure indexes and per capita income in the country pairs (as included in the OECD’s work) would reduce the number of countries for which transport costs could be estimated. GFI’s work follows the OECD’s decision to restrict the Comtrade data included to only “reliable” observations, a step not included in the CEPII work (Specifically, GFI followed the OECD in including in the statistical model only those matched trades for which: (a) the associated trade volumes differ by less than 5 percent, and (b) the ratio of the import price per unit (CIF) to the corresponding export price was not less than 1 and not greater than 2). The OECD argues persuasively that CEPII’s inclusion of all matched transactions (including those for which import prices were below the associate export prices) biased downward CEPII’s estimated CIF/FOB margins.) GFI’s estimated equation qualitatively supported the findings of both the CEPII and OECD research. GFI’s research on transport margins is work still in progress. A more detailed presentation of GFI’s estimated model of transport margins used here is available upon request.

Shrinkage adjustments to enhance robustness and reliability

In order to reduce the distortionary effects of statistical outliers in the data, GFI applies a weighted formula. The use of weighted measures (rather than the raw trade gaps) in the Comtrade estimates is intended to improve the reliability of the trade misinvoicing estimates. The weighting scheme is described in formal terms as follows: Let QD and QA denote, respectively, the reported volume of trade (of a particular good in a particular year) between a developing country reporter (D) and its advanced-country trade partner (A). The weight applied to the trade gap in value terms was specified as the following: {1 – |QD – QA|/max(QD,QA) }. It should be noted that a different weight will apply to every matched record in Comtrade; for a given developing country, the weights will vary over time, by commodity traded and by trading partner. This weighting scheme, frequently used in the literature, effectively shrinks the arithmetic value of the dollar-denominated trade gap by a factor that increases as the associated volume gap rises. That is, the dollar value of a dollar-denominated trade gap is assigned a higher value the closer the associated matched volume reports are; conversely, a larger volume discrepancy means a lower weight was placed on the dollar-denominated trade gap. Generally, this might be interpreted as a reliability weight for set of matched values in the Comtrade data; in effect, highlighting trade gaps that appear more likely to be due to misinvoicing. Other interpretations of this weighting scheme are possible. Additionally, other specifications for such weighting are possible; see, for example, Ten Cate (2007) and Gaulier & Zignano (2010).