Need Funds for the SDGs? Tackle Trade Fraud

By Tom Cardamone, July 9, 2019

As scores of government representatives gather at the UN this morning for 10 days of high-level discussions on the current progress of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the elephant in the room is how developing and emerging market countries will pay for the services required to achieve the scores of targets contained in the SDG agreement.

Equally criticized as too expansive, or praised as sufficiently aspirational, the SDGs are the internationally agreed upon roadmap for global development up to 2030. A critically important – and widely unrecognized – component of the agreement is that the bulk of the estimated $1.4 trillion needed annually to achieve the SDGs is expected to come from the developing countries themselves. Four years into the 15-year SDG timeline, it is clear that this revenue target will be a heavy lift for many of the less developed nations.

Massive tax evasion through profit shifting by multinational corporations (MNCs) has drained billions of dollars from developing countries and, if addressed, is seen by governments, civil society and multilateral institutions as a key source of funds for global development. Indeed, outgoing Managing Director of the IMF Christine Lagarde wrote in March that developing countries “collectively lose about $200 billion in revenue a year, or about 1.3 percent of gross domestic product” due to the manipulation of profits by huge global companies.

In a positive step forward, G20 finance ministers have begun to overhaul global tax rules as they apply specifically to tech firms. But the devil is in the details. A formal agreement is not likely until next year and it won’t address the broader profit shifting problem by companies operating in developing countries (beyond those in the G20). Additionally, efforts by an array of countries and civil society groups to make the UN the preeminent global tax rules-setting body, and thereby give developing countries a much needed stronger voice in MNC tax policy, is currently an uphill battle that could take years before significant changes take effect.

A more immediate source of critically-needed SDG funding could be found by helping developing country governments capture revenue lost to an activity known as trade misinvoicing – more commonly called trade fraud. Trade misinvoicing is the deliberate falsification by importers and exporters of the value, quantity or type of goods being shipped internationally as a way to evade import duties, VAT and other taxes.

Research by Global Financial Integrity (GFI) shows that the gap between the reported values of goods imported by and exported from developing countries, versus the values reported in their advanced country trading partners, is equal to 18 percent of that trade, or close to $1 trillion per year. Most importantly, the associated lost revenue to developing country governments due to misinvoicing is estimated to be at a magnitude similar to the IMF’s tax evasion figure for MNCs.

As developing country customs departments often don’t have accurate information regarding the value of the goods being reported to their advanced country counterparts, they don’t have a clear sense of what they’re losing. Additionally, the ease with which invoices can be manipulated in developing countries is startling. Senior customs department officials from several countries have told GFI they estimate 80 percent of invoices submitted by importers are falsified, indicating that this problem is severe, chronic and ubiquitous in countries where revenue from trade is vitally important to the economy.

Given the magnitude of trade misinvoicing, multilateral financial institutions and governments that provide development assistance should examine the potential of trade risk-assessment tools – databases that enable customs officials to detect when misinvoicing occurs – on a broad scale so as to help as many nations as possible capture lost funds.

GFI works with developing country governments by providing an easy-to-use, cloud-based risk assessment tool, GFTrade, designed to help customs departments detect international trade transactions that indicate misinvoicing. This tool enables users to quickly determine whether goods being imported or exported are priced outside average price ranges for comparable commodities, increasing customs clearance efficiency and risk management that arises through asymmetry of information in international trade transactions. This empowers governments to collect tens of millions of dollars in additional custom duties that would have otherwise gone undetected.

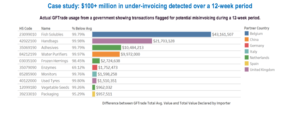

In one particular case, GFI helped a government identify more than $100 million in under-invoiced imports in a 12-week period:

While addressing this challenge alone won’t completely fill the SDG funding requirements – that will require massive inputs from several sources – this is an effort that can bolster a government’s ability to raise significant amounts of funds for the SDGs today, without the difficulties associated with multilateral (and multi-year) negotiations.

An added benefit of this approach to revenue collection is that it will empower developing country governments to immediately address a problem that is highly corrosive to their economies. A simple database can put governments in the driver’s seat by enabling them to identify trade fraud in real time. Developing countries can’t afford to wait for significant changes to global tax rules before they start capturing revenue being lost every day.

The success of the SDGs and the health and lives of people around the globe depend on it.