The Business of Transnational Crime

By Channing Mavrellis, April 11, 2017

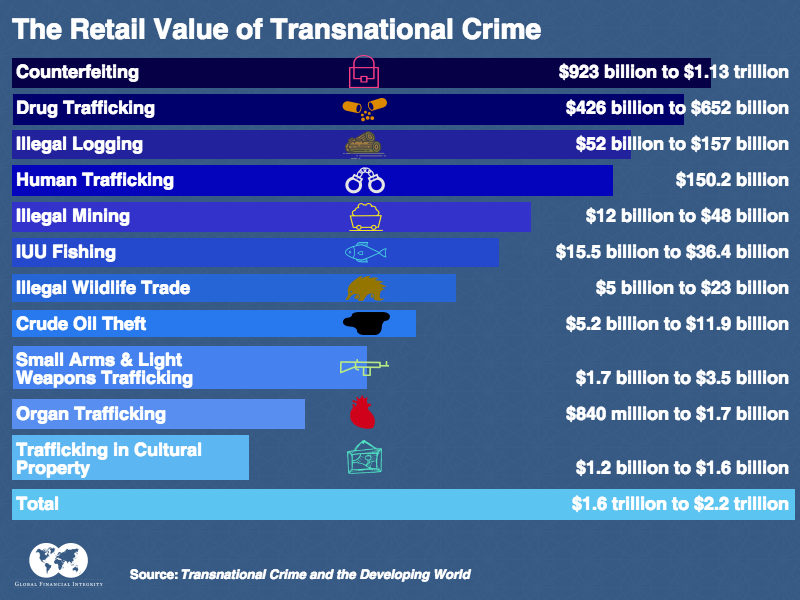

The groups engaged in transnational organized crime—from criminal networks to insurgent groups to terrorist organizations—are united by a common thread: money. All of the crimes covered in Global Financial Integrity’s new report Transnational Crime and the Developing World are overwhelmingly profit-motivated. Globally, transnational crime has an average annual retail value of $1.6 trillion to $2.2 trillion, based on 11 “industries”: counterfeiting and piracy, drug trafficking, illegal logging, human trafficking, illegal mining, illegal fishing, the illegal wildlife trade, crude oil theft, the trafficking of small arms and light weapons, the illegal organ trade, and the trafficking of cultural property.

What’s often overlooked is that many of the groups engaged in transnational crime are businesses. They are organized commercial entities that provide goods and/or services to consumers, it just so happens that these goods and services are illegal or illegally obtained. Some of these groups are so well organized and well funded that they rival legitimate multinational corporations: they are the incorporation of transnational crime.

This is not an isolated phenomenon; there is a consistent pattern of criminal enterprise across all of the criminal markets we studied. Look at the amount of control that Mexican drug trafficking organizations now have on drug trafficking—from the cultivation and production of cannabis, cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine, to their distribution around the globe. Or their diversification into other criminal activities, such as illegal mining, illegal logging, and crude oil theft, among others. Look at Nigerian or Italian or Chinese organized crime groups (OCGs), who have taken their (criminal) business model worldwide.

To effectively combat transnational crime, policy makers and law enforcement need to stop treating these groups as distinct entities. They need to stop thinking of these groups in emotional terms of good versus evil and must remember that these are businesses.

Traditional law enforcement responses have met with limited success, particularly in regard to the war on drugs. Frequently, these efforts focus on interdicting the participants and the products. But what if we were to use these same methods to try and shut down a legitimate company, for example Apple?

One popular tactic employed by law enforcement is to go after the leaders, or heads, of criminal organizations, what’s known as a decapitation technique. But this approach has had hardly any success, and the Apple example illustrates one of the reasons why. Steve Jobs was a visionary leader and instrumental to the creation of the Apple brand. Yet his death had very little impact on the company—the brand and its products were well established and in strong demand.

With criminal groups moving away from hierarchical, vertically-integrated organizations, this technique does not have the same type of impact it used to have. In addition, there are many instances of criminal groups, particularly gangs in Latin America, whose leadership has been imprisoned with minimal impact to the group’s activities. The leaders, such as those from Mara Salvatrucha, are still able to control and even expand operations from within prison.

Law enforcement also goes after low-level participants—the street-level dealers, the poachers, the informal miners, and sometimes even the sex trafficking victims. Try shutting down Apple by arresting employees at their stores: you have removed those who are responsible for the direct sale (or acquisition) of goods, but this is a temporary win. They are easily replaced, and, more importantly, they play a minor role.

Another common enforcement method is to go after the product, from dime bags of cannabis to tons of pangolin scales. Can you imagine thinking that a good way to force Apple out of business is by seizing every iPhone or iPad? It would be an exercise in futility—there are billions of Apple products out there, and billions more being manufactured thanks to strong global demand.

I’m not saying that we should ignore the people and products, but so far these methods have not proven to be sufficient in seriously curtailing transnational crime. Targeting the superficial symptoms of transnational crime, rather than attacking the underlying system that supports it, won’t provide long-lasting, substantive results.

Transnational crime is greater than the products and people involved—it is a systemic problem

So what is one thing that businesses—legal or illegal—need to survive? Money. They need access to it to cover the costs of their operations, and they need a way to clean and transfer their profits across borders. OCGs aren’t charities—if they can’t make an acceptable profit, they’re not going to continue operating in a given market. This is why Global Financial Integrity emphasizes that “profit-motivated crimes require profit-oriented responses.”

When it comes to the money generated by transnational crime, the conversation has often stalled on the point that these revenues line the pockets of criminals. What’s often not mentioned is that, like legitimate businesses, OCGs also reinvest their profits back into their business, improving and expanding operations, as well as diversifying into other illegal activities.

We need to see going after the money as more than just preventing criminals from enjoying their profits—it is an essential part of attacking the funding that allows and encourages such groups and networks to keep operating.

Governments need to ensure that strong anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) laws and regulations are in place and, more importantly, effectively enforced. We need to increase our efforts in combatting the global shadow financial system, which is used for all transnational crime: things like trade misinvoicing, anonymous shell companies, and secrecy jurisdictions.

Advocating for strong AML/CFT laws and enforcement, the collection of beneficial ownership information, increased scrutiny of secrecy jurisdictions, monitoring cross-border trade for invoice fraud, and increased inter-agency data sharing should be the new rallying cry of those seeking to combat transnational crime and its associated ills.